자유시(Free verse; Vers libre)

A.

전통적인 의미에서 시가 압운체계(rhyme scheme)와 명시적 운율(meter)을 바탕으로 하지만, 자유시는 무압운, 비운율의 ‘열린 형식’의 시이다. 자유시란 운율시(metrical verse)의 파생 장르(즉, 시)이면서도 ‘운율 피하기’(즉, 자유)라는 의미에서 용어상 모순이지만 동시에 다양한 작시법이 혼합된 형태이다. 자유시는 시의 일반 규칙과 제약을 거의 받지 않고, 그 시적 효과를 주로 개별적 리듬과 불규칙해 보이는 시행에 의존한다. 자유시는 압운체계가 없다는 점에서 무운시와 유사하지만, 무운시와는 달리 약강5음보의 운율형식을 따르지 않는다. 또한 자유시는 행 배열이외에는 산문과 본질적 차이가 없지만, 압운이 없지만 내재율을 가진 운문이라는 점에서 산문체 리듬에만 의존하는 산문시(prose poems)와도 다르다. 자유시는 기본적으로 시행이 리듬 단위이며, 규칙적 음보와 뚜렷한 압운이 없기 때문에 구문이나 억양과 같은 내적 논리에 따라 유기적으로 구성된다. 연 구성 또한 의미 단위로 이뤄짐에 따라 길이가 제각각이고 시각적으로 특이해 보이는 경우도 있다. 그 결과 자유시는 극단적으로 다양한 형태를 띠는데, 이를 통해 실제 삶의 경험을 보다 사실적으로 재구성한다. 삶의 지각, 인식, 정서, 상상의 과정을 복제, 투사, 재현 하려는 자유시 정신이 시인과 독자를 끊임없이 매료시키는 요소이다. 즉, 자유시는 정해진 형식이나 외적 규범이 없어서 시인의 개성이 보다 분명히 확보되고, 시의 속도, 강세 등을 창출하기 위해 독자의 개입이 보다 적극적으로 요구되는, 오늘날 가장 보편적인 유형의 시이다.

B.

자유시는 인류의 구어 전통에 바탕하여 규칙적 운율 이전으로 거슬러 올라가는 세계 문학사상 일찍부터 발견되는 가장 오랜 시 형식 중 하나로서, 서정시 전통에 그 맥이 닿아있다. 민족에 따라 서로 다른 역사적 조건을 갖고 있는 만큼 그 스펙트럼이 넓고 운율 배경도 다양하다. 그럼에도 자유시는 압운체계와 운율형식이 지배해온 문학사에서 오랫동안 억압되어 오다가 20세기 이미지즘, 아방가르드 같은 모더니즘 자유시로 ‘억압의 귀환(the return of the repressed)’을 이뤄낸다. 용어상 자유시는 엄격한 전통운율로부터 부분적으로 자유로워진, 17세기 프랑스 라퐁텐(La Fontaine)과 그의 동료들의 해방된 시(vers libéré)를 기원으로 한다. 그러나 오늘날 우리가 알고 있는 자유시라는 명칭은 대체로 파격적 기법으로 불규칙한 운율을 시도한 귀스타브 칸(G. Kahn)이나 쥘 라포르그(J. Laforgue) 등과 같은 19세기말 프랑스의 시인들의 시작 활동에서 기인한다. 영어권에서 자유시는 오래전부터 비하의 표현으로 쓰이다가 20세기 초 문학운동의 구호로 등장한 후 중립적인 기술어(記述語)가 되어 오늘에 이른다.

영문학에서 현대적 의미의 자유시는 이미 1611년 흠정역 성경(the King James Bible)에 나타난다는 인식이 일반적이다. 그중 시편(Psalms)과 아가서(the Song of Solomon)는 고대 히브리 시가의 병행구조와 카덴스(cadence)를 산문 영어로 모방한 것이다. 특히 시편은 1380년대 위클리프(J. Wycliffe)이래 오늘날까지 다양한 형태의 자유시로 번역돼왔다. 이와 같은 성경의 문체는 18세기 중반 크리스토퍼 스마트(Ch. Smart)의 장편 자유시 『어린양을 기뻐하라』등에 영향을 미쳤다. 그러나 자유시는 19세기 많은 영미 시인들의 형식실험을 통해 발전된다. 윌리엄 블레이크(W. Blake), 매슈 아널드(M. Arnold) 등은 규칙적 음보에서 벗어난 문체를 구사하고, 크리스티나 로제티(Ch. Rossetti), 코벤트리 팻모어(C. Patmore), 브라운(T. E. Brown) 등은 정해진 격식이 없는 압운시를 시도했다. 그중에서도 미국시인 월트 휘트먼(W. Whitman)은 현대 자유시의 중요한 선구로 알려진 비운율시 『풀잎』을 썼다. 그의 문체 역시 성경을 바탕으로 하고 있는데, 특히 강세와 음절수의 규칙을 무시한 다양한 길이의 시행으로 세상을 놀라게 했다. 그는 구어에 바탕한 형식을 통해 예기치 못한 곳에 강세를 둘 뿐 아니라 문법적 강조, 평행구조, 전후 조응(anaphora, 특히 첫머리 어구반복), 산문처럼 긴 시행 등을 영시에 되살렸다. 반복되는 음보를 통해 리듬효과를 창출하는 전통시와는 달리 그는 특정 낱말, 구, 절, 시행 등 의미 단위의 반복, 균형, 변주 등을 효과적으로 활용했던 것이다. 휘트먼 이후 영어권 자유시는 대체로 번역 성경에 기원한 긴 시행으로부터 짧은 대화체로의 이행 과정이었다. 그밖에도 전통적 작시법에서 벗어나려는 시도는 낭만주의 이래 대부분의 서구 민족문학의 주요 경향을 이룬다. 러시아의 수마로코프(A. P. Smarokov), 푸시킨(A. S. Pushkin), 독일의 괴테, 횔더린(F. Hölderlin, 프랑스의 랭보(A. Rimbaud), 아폴리네르(G, Apollinaire) 등이 민족 고유의 운율에서 근본적으로 벗어난 시를 썼다. 특히 독일의 하인리히 하이네(H. Heine)는 연작시 「북해」를 통해, 그리고 랭보는 산문모음집 『일루미나시옹』을 통해 자유시의 발전에 크게 기여했다.

오늘날 자유시는 대체로 19세기말 프랑스의 상징주의시와 1차세계대전 전후 아방가르드 자유시를 의미한다. 이 시기의 자유시는 자의식적이고 자기선언적이며 운율에서 보다 철저히 자유로워지려는 시도였다. 20세기 초 영어권의 이미지즘 시인들은 습관적으로 시행과 문법적 단위를 일치시켰고, 이 운동과 직간접적으로 연관된 에즈라 파운드(E. Pound), 엘리엇(T. S. Eliot) 등도 다양한 형태의 자유시를 실험했다. 이후에도 앨런 긴스버그(A. Ginsberg)나 로버트 블라이(R. Bly)의 목록시(the catalog verse), 칼로스 윌리엄즈(W. C. Williams)의 변동음보(the variable foot) 이론, 찰스 올슨(Ch. Olson)의 투사시(the projective verse) 등을 통해 자유시를 실천하고 또한 이론적으로 옹호했다. 문학사에서는 아방가르드 자유시는 불어권의 랭보, 브르통(A. Breton), 에메 세자르(A. Césaire) 등과 칠레의 스페인어 시인 파블로 네루다(P. Neruda), 영어권의 찰스 톰린슨(Ch. Tomlinson) 등이 대표한다.

20세기 자유시는 그 다양성 때문에 일반화할 수 없다. 그럼에도 많은 유형의 자유시에는 운율시 못지않은 규칙성이 존재하는데, 전통시와의 차이점은 단지 그 규칙이 개별시의 언어와 텍스트 논리에 바탕한다는 점이다. 오늘날 자유시는 내재율이 지배적이지만, 시인들은 필요에 따라 해방된 형식을 통해 운율시와 자유시 사이를 수시로 넘나든다. 심지어는 20세기말 신형식주의로 알려진 몇몇 시인 비평가들처럼 전통적 작시법의 음보, 압운, 연 형식 등으로 돌아갈 것을 주장하는 경우도 있다.

C.

자유시는 그 대중성과 성취에도 불구하고 그 가능성과 한계에 대한 지적도 있다. 실제 시작 과정에서 특별한 형식적 제약이 없고 개별적, 내적 통제에 따라 전개되는 자유시가 갖는 곤경을 프로스트는 “네트 없이 테니스 치기”(playing tennis without a net)라는 은유를 통해 드러낸다. 그러나 자유시가 여전히 시로 인식되는 한, 나름의 구조와 리듬을 가지며 전통적인 운율시의 경우와 동일한 용어 및 방법으로 논의될 수밖에 없다. 그런 의미에서 엘리엇의 지적처럼, “시를 잘 짓고자하는 자에겐 어떤 시도 자유롭지 않다”고 할 것이다. 자유시는 외부에서 주어진 규칙이 없다 해도 여전히 어구반복, 약하나마 압운, 평행구조, 대조, 콤마 등을 통해 반복과 반향을 일으켜 리듬을 형성하고, 유사한 이미지나 낱말을 나열하여 음악적 효과를 내기 때문에 문장강세 운율(intonational metre)이라 불리기도 한다. 그럼에도 자유시는 운율 규범의 의도적 배제와 문장을 문법 혹은 의미단위로 분절한 시행을 주요 특징으로 한다. 또한 자유시에서는 구조상 반복 못지않게 일회적 우연성이 중요하며, 시적 효과를 문법과 서로 다른 길이의 시행이나 연 사이의 긴장에 의존한다. 그 결과 자유시는 주어진 규범보다는 개별 시의 임의적 요소가 부각되고, 주로 청각에 기대는 정형시와는 달리 시마다 서로 다른 시각적 공간을 창조한다. 자유시는 시형식을 유지하면서도 시마다 독특한 형태와 예측 불가능한 구조의 역동성을 통해 한편으로 시 장르의 연속선상에서 놓이면서 다른 한편 수사적 측면에서 끊임없는 ‘낯설게하기’를 시도한다.

대부분의 자유시는 전통시처럼 시행의 관행을 따르지만, 시행의 길이를 규제하는 원칙이 없기 때문에 서로 다른 길이를 통해 다양한 효과를 창출한다. 문법, 의미, 시각 단위의 어구로 시행을 구분함으로써 일률적인 정형시행의 단조로움을 벗어나 보다 짜임새 있는 구성이 가능하다. 반면 상투적 문법, 의미, 시각 단위 안에서 시행갈이를 폭력적으로 시도하는 경우는 전치사나 조사와 같은 기능어를 강조하여 파편화 혹은 탈자동화된 불연속적 읽기를 요구한다. 대체로 짧은 시행이 단절효과를 일으켜 흐름을 조절하고 무게를 보태는 반면, 긴 시행은 5음보 같은 전통적 시행의 한계를 넘어서는 탄력을 준다. 길이가 짧든 길든 등가의 시행으로 이뤄지는 자유시에서는 대체로 어떤 두 행의 길이도 일치시키지 않는데, 확장된 서사시나 짧은 서정시에서 긴 시행과 짧은 시행을 교차시켜 대화적 효과를 낼 수 있다.

자유시에서는 시어 또한 소리와 시각효과로 풍부한 의미를 형성하지만, 그 효과는 대체로 일회적이다. 가령 자유시에 압운이 나타난다 해도 시 전체 구도로서가 아니고 단어와 시행의 중간처럼 예상치 않은 곳에서 우연적 상황으로 종종 발생한다. 반면 자유시는 시각적 효과를 위해 한 페이지 전체에 걸쳐 시를 배치하기도 한다. 예를 들면 말라르메(S. Mallarmé)는 『주사위 던지기』에서 새의 깃털모양을 제시하기 위해 펼칠 수 있는 확장된 페이지를 사용하기도 한다. 이 경우 여백이 텍스트를 둘러싼 공간으로서 멈춤, 분리, 침묵의 이미지 등을 창출한다. 또한 자유시에도 다른 시의 경우처럼, 인쇄 기술과 새로운 시각 매체의 발전으로 시각적 장치에 영향을 받아왔다. 자유시는 타자기 자판이나 조판 상 가능한 상징이나 문자를 이용함으로써, 실제로 운율파악을 불가능하게 하거나 운율을 파괴하기도 한다.

참고문헌

Meyer Howard Abrams, Geoffrey Harpham, A Glossary of Literary Terms, Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

Antony Easthope, Poetry as Discourse, Methuen, 1983.

Thomas Stearns Eliot, “Reflections on Vers Libre” Selected Prose of T S Eliot, Ed. Frank Kermode, Faber 1975.

Harvey Seymour Goss, Sound and Form in Modern Poetry, U of Michigan P, 1964.

Alex Preminger, Terry Brogan et al (eds.), The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, Princeton UP, 1993.

Lecture Note on Benjamin's 'Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility'

Walter Benjamin (1892-1940)

The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility(Third Version, 1939)Central Question:

Under the twentieth-Century conditions of capitalist production and reproduction, how has art developed, and how has it been affected by those conditions?

•A shift in attitudes to art as a result of the introduction of technological means of reproduction:

Because of technological mass reproduction, art has lost its ‘authenticity’ in the capitalist-oriented culture industry of the 20th Century.

•This loss of authenticity is not so bad, for it democratises and politicises art.

5 main ideas:

1) To an ever-greater degree the work of art reproduced becomes the work of art designed for reproducibility. (256)

2) The film responds to the shrivelling of the aura by artificially building up the ‘personality’ outside the studio. (261)

3) The equipment-free aspect of reality has here become the height of artifice, and the vision of immediate reality has become the Blue Flower in the land of technology. (263)

4) Magician is to surgeon as painter is to cinematographer. (263)

5) On the one hand, film furthers insight into the necessities governing our lives by its use of close-ups, by its accentuation of hidden details in familiar objects, and by its exploration of commonplace milieux through the ingenious guidance of the camera; on the other hand, it manages to assure us of a vast and unsuspected field of action. ... With the close-up, space expands; with slow motion, movement is extended. (265)

In short, the main arguments are:

Culture itself has been transformed into an industry; art has therefore become commodified.

Contemporary culture shows how oppressive ideologies are reproduced and disseminated.

New media technologies such as phonographs, epic theatre, and especially film and photography, not only destroy art’s ‘aura’ but demystifies the process of creating art, making available radical new access and roles for art in mass culture.

The spectator has become a participant, or collaborator, who joins the author in deciding meaning in the production of the work of art. In this process, art is ‘successful’ only when it allows critical contemplation by the viewer. This is the profoundly democratic aspect of these new developments.

Key Concepts: The original vs. the copy

The aura (authenticity)

The mass

The critic/expert

Cult value vs. Exhibition value

Progressive reaction (reactionary or fascist vs. progressive or revolutionary)

Distraction

Dadaism

Discussion Questions

1. What fundamental cultural shift does the mass (technological) reproduction of art initiate by replacing earlier conditions of producing and consuming artworks?

2. What kind of relationship is there between photography and cinema? Does photography gradually culminate in the moving images of cinema or imply cinema (ie, foreshadow it from the beginning)?

3. What does Benjamin say about the intersection of aesthetics and politics under Fascism?

Introduction: Kunstpolitik or, the Historical Materialist Perspective on Reproduction [251]

The impact on art of the mass technologies of reproduction (photography/ film):

implications on the theory of art

implications on the existing politics of art (Fascist, socialist)

the revolutionary demands on the Kunstpolitik

The task of Marxist historico-dialectical materialism under advanced modernity:

Theses defining the developmental tendencies of art [as a kind of superstructure] under the present conditions/modes of production [the economic base] can contribute to the political struggle in ways that it would be a mistake to underestimate. [252]

- the manipulations of art in the hands of Fascists (current tendencies)

- the nature of the proletariat art and art as weapon in class struggle

(For the superstructure changes much more slowly than the base, with the effect that cultural phenomena always lag behind the conditions that produce them. For this reason, Benjamin observes the conditions of present culture at the point of their earliest development with an eye for the present state of productive (and reproductive) technologies. He tries to draw attention to changes in the conditions of production as a way of intervening in the process. His theses are, thus, intended as weapons in the war against fascism.)

What would Benjamin argue against the formalist method? Why wouldn’t he accept the way they delineate textual ‘objects’ and then analyse those objects?

I. A Brief History of Reproduction [252]

Reproducibility varies with different historical periods:

Casting and stamping (uniqueness not threatened; limited uses)

Woodcut graphic art (mechanical reproduction of text & images)

Printing as the technological reproducibility of writing

Engraving and etching (images, maps, music) (in the Middle Age)

Lithography (to provide an illustrated accompaniment to everyday life) (in the early 19th C.)

Photography (from hand to eye) (in the late 19th C/early 20th C)

Film (the process of pictorial reproduction could now keep pace with speech)

A qualitative shift around 1900:

Technological reproduction reached a standard that not only reproduced all known artworks, profoundly modifying their effects, but captured a place of its own among the artistic processes. [253]

(Before, the reproduction of an artwork was imitation. Now the reproduction goes beyond 1-1 imitation so much that it is important to think about what it means. When you can have hundreds of lithograph reproductions of almost the same quality of the original, where is the value in the original? And what about those works (such as film) that are made to be reproduced?)

The impact which the reproduction of artworks and the art of film are having on art in its traditional form

What can technological reproduction do? To capture images that escape natural vision (photography)

To put copies of the origin in situations out of reach of the original itself

To produce copies more independent of the original

To depreciate the value of the original

II. Effects of Technological Reproducibility: the Original vs. the Copy [253]

The importance of uniqueness as a prerequisite to authenticity and aura in the original (on whose existence the copy’s reproduction and worth depend):

The technological processes of reproducibility are bringing about the disappearance of das Hier und Jetzt of an artwork, its unique existence in a particular place.

(Detaching the Reproduction from the Original •means we’re attached to a likeness •destroys the ‘aura’ of the original •increases the sense of the universal equality of things)

The Disappearance of an object’s authenticity:

The authenticity of a thing is the quintessence of all that is transmissible in it from its origin on, ranging from its physical duration to the historical testimony relating to it. [254]

(Authenticity is then important and it is measured in space and time. However, the reproduction is ‘freer’ to be placed in situations in which the original cannot be placed.)

· The symptomatic loss of an object’s aura

‘aura’: (unique existence; tied to physical presence; domain of tradition)

- customary historical role played by the works of art

- their ‘ritual function’ in the legitimation of traditional social formations

· With the technology of reproduction the copy is detached from the sphere of tradition (and its originary aura).

- By replicating the work many times over, it substitutes a mass existence for a unique one.

- In permitting the reproduction to reach the recipient in his own situation, it actualises that which is reproduced.

The social significance of film … is inconceivable without its destructive, cathartic side: the liquidation of the value of tradition in the cultural heritage.

Reproduction raises questions about the purpose of art

(Another value of the original is tradition. The reproduction refers the viewer to the original. However all this originality came into crisis with works of art made with the new traditions of technological production, as works of art can be made to be reproduced. As such then art was released from tradition. And art for art's sake was born. It no longer talks about social functions, but it instead talks about itself. What is interesting is that the loss of ritual and the artwork for reproduction also makes it political. The value of art is to be measured in terms of cult value or it's exhibition value.)

How does technological reproducibility destroy the ‘aura’ of a work of art? How does Benjamin explain what he means by the term ‘aura’?

When is it possible to recognise ‘authenticity’? Can there be any authenticity without its destruction in technological reproducibility? Do you agree with the statement that the idea of authentic art only emerge when authenticity is a threatened species of artwork?

III. A Decay of the Aura as the Human Collectives’ Mode of Sense Perception, or Massification [255]

How human sense perception is organized depends on the historical circumstances, and the decay of the aura can be explained by its social determinants:

· If changes in the medium of present-day perception can be understood as a decay of the aura, it is possible to demonstrate the social determinant of that decay.

(the aura of a natural object as the unique apparition of a distance, however near it may be [255])

(Unlike in the experience of nature, technologically reproduced images, if perfect ones, are missing das Hier und Jetzt of the object which gives it its aura. The difference is like the loss of das Hier und Jetzt of an actor in the passage from stage to screen. But what Benjamin would argue is that cinema makes so much more possible than the stage can do.)

· The increasing significance of the masses in contemporary life and the desire of the masses to bring things ‘closer’ spatially and humanly and therefore overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by assimilating it as a reproduction (the railway mania, tourist snapshots)

· The stripping of the veil from the object, the destruction of the aura, is the signature [mark] of a perception whose ‘sense of sameness in the world’ has so increased that, by means of reproduction, it extracts sameness even from what is unique. [255-56]

· Field of perception mirrors the field of organization of social life (cf. the increasing importance of statistics)

The alignment of reality with the masses and of the masses with reality [under modernity] is a process of immeasurable importance for both thinking and perception. [256]

Why does the masses embrace the destruction of the auratic quality of works of art?

IV. Art Past and Present: from Ritual to Politics [256]

Tradition is an interpretive framework for an auratic object, but tradition is alive and changeable:

- The embeddedness of an artwork in the context of tradition found expression in a cult (in the service of rituals—first magical, then religious).

e.g., the aura of an ancient statue of Venus both in classical Greece (as an object of worship) and in medieval Europe (as a sinister idol)

- Renaissance distinct historical interpretations of the object: ritual vs. art

A History of the Aura:

- From Art as embedded in Tradition to Technologically Reproduced Art

· The artwork’s auratic mode of existence is never entirely severed from its ritual function.

The unique value of ‘authentic’ work of art has its basis in ritual, the source of its original use value

· The ritualistic basis, however mediated it may be, is still recognisable as secularised ritual in even the most profane forms of the cult of beauty.

· The Renaissance: (Art emancipated from ritual)

Secular worship of beauty developed and prevailed for the following three centuries

(the ritualistic basis in its subsequent decline but art remains auratic)

· The mid 19th C: (Criterion of authenticity does not apply)

l’art pour l’art = a theology of art (a negative theology, in the form of an idea of ‘pure’ art, which rejects not only any social function of art but any definition in terms of a representational content)

· The late 19th C: (photography emerging at the same time as socialism)

The work reproduced becomes the reproduction of a work designed for reproducibility [256];

The criterion of authenticity ceases to be applicable to artistic production and the whole social function of art is revolutionised [256-57]

(Instead of being founded on ritual, it is based on a different practice: politics)

· The 20th C: massification (Art is then based more on politics)

Why is Benjamin so opposed to l’art pour l’art? (And what relationship between producer, receiver, and art object does this doctrine maintain?)

V. From Cult Value to Exhibition Value: A Quantitative Shift Led to a Qualitative Transformation [257]

Two polar types of value in the reception of artworks and the ability to reproduce objects through different methods of technological reproduction:

Cult value decreases: The work of art was created as an instrument of magic (ie, a religious object)

Artistic production begins with figures in the service of a cult.

- their presence mattered, not their being seen (Altamira cave paintings)

With the ability to reproduce objects, they would have to be kept out of sight in order to maintain their cult value

Absolute emphasis on the cult value with limited reproducibility in prehistoric times

Exhibition value increases: The instrument of magic came to be recognised as a work of art.

With the emancipation of specific artistic practices from the service of ritual, the opportunities for exhibiting their products increase (in museum and inevitably in cinema).

- The scope for exhibiting artworks has increased enormously with the various methods of technological reproduction.

- Through the absolute emphasis on its exhibition value, the work of art becomes a construct with quite new functions (e.g., the artistic value).

Photography and film are the most serviceable vehicles of massification, or displacement of cult value.

Art assumes entirely new functions in circulation

What are the differences between art created for its cult value and art produced for its exhibition value?

VI. Art at the Crossroads of Cult Value and Exhibition Value: Photography and Film [257]

Exhibition value in photography drives back cult value on all fronts:

The human countenance (the portrait) as a vestige of cult value in early photography (the cult of remembrance of dead or absent loved ones) [257-58]

- In the fleeting expression of a human face, the aura beckons from early photographs for the last time. [258]

As the human being withdraws from the photographic image, exhibition value for the first time show its superiority to cult value

- Atget around 1900 – photographs of deserted Paris streets

(scenes of crimes to establish evidence—photographic records—hidden political significance—a specific kind of reception—no fee-floating contemplation)

- Illustrated magazines (captions are introduced as directives to images/altogether different from the titles of paintings)

- Film (in which the directives given by captions are even more precise and commanding) in which the meaning of each single picture appears prescribed by the sequence of all the preceding images

VII. The Ill-Considered Standpoints on Photography and Film (Contradictions of Film and Art) [258]

The 19th-C dispute over the relative artistic merits of painting and photography: Is photography art?

(an expression of world-historical upheaval)

· If the age of technological reproducibility separated art from its basis in cult, all semblance of art’s autonomy disappeared forever.

- The invention of photography transformed the entire character of art forever. [258]

The early 20th-C disputes on the nature of film

(a desire to annex film to ‘art’ and to attribute elements of cult to film) [259]

- A sacred and supernatural significance or the sterile copying of the exterior world?

· Film = a step further in the process of representation close to reality

Film has ‘its unique ability to use natural means to give incomparably convincing expression to the fairylike, the marvellous, the supernatural (Werfel)’.

Film is auratic, but its exhibition value is stronger than art.

What does Benjamin describe as some reactionary ways of resisting the camera’s potential to revolutionise people’s sensibilities?

VIII. The Performance Direct and Mediated: Stage vs. Screen [259]

The artistic performance of a stage actor

- directly presented to the public by the actor in person

- with the opportunity to adjust [and react] to the audience during performance

- allowing the audience to have direct access to performance

The artistic performance of a screen actor

- presented through the technological apparatuses (the camera and the recording one)

- subjected to a series of optical tests (camera views and editing)

- with constantly changing audience taking the position of a critic without experiencing any personal contact with the actor [260]

- The audience’s empathy with the actor is really an empathy with the camera

(the position of the camera = the position of the audience => testing (of work) approach)

not an approach compatible to cult value but commodification of actors and cult of celebrity

What does the camera do to the actor of a film role?

What happens to the real person’s stage presence (an auratic quality if the actor is in front of a live audience in, say, a drama) once the camera captures the performance on film?

IX. The Decay of the Aura as the Effect of Film (Art Bound by Technology) [260]

The actor represents himself before the apparatus. [260]

(He is very often denied the opportunity to identify himself with a role. [261])

The Artificiality of Film:

- The actor operates with his whole living person, yet forgoing/sacrificing its aura. [260]

(The aura is bound to his presence in das Hier und Jetzt —there is no facsimile/replica of the aura.)

- Art is completely subject to or founded in technological reproduction.

(‘the best effects are achieved by “acting” as little acting as possible’ in film. [260])

- An actor as stage props chosen for his typicalness and introduced in the proper context;

His performance split into a series of episodes capable of being assembled [261]

Art has escaped the realm of the ‘beautiful semblance’, which for so long was regarded as the only sphere where art could thrive.

X. The Historical Significance of the Film Industry Today [261]

Resulting in the loss of the aura of the person:

The feeling of estrangement before one’s appearance in the mirror

- The mirror image has become detachable and transportable from the person mirrored to a site in front of the public, the consumers who constitute the market beyond his reach.

- Film responds to the shrivelling/withering of the aura by artificially building up the ‘personality’ outside the studio.

- The cult of the movie star fostered by the film industry does not preserve the unique aura of the person but the putrid/decaying magic of the personality’s own commodity character.

However, the ease of replication has other advantages:

- Today’s cinema promotes a revolutionary criticism of traditional concepts of art, social conditions, even of property relations. [261-62]

- The possibility of participation - to be reproduced

(e.g., the newsreel that offers everyone the chance to rise from passer-by to movie extra)

A person might even see himself becoming part of a work of art. Any person today can lay claim to being filmed.

The historical situation of literature today: [262]

- In literary marketplace, the reader gains access to authorship; the distinction between author and public is about to lose its axiomatic character.

- Literary competence is no longer founded on specialised higher education but on polytechnic training, and thus is common property.

In film, shifts that took place in literature over centuries have occurred in a decade. [262]

- The film industry has an overriding interest in stimulating the involvement of the masses through illusionary displays and ambitious speculations. [263]

How does Hollywood hold the transformative potential of film captive to the imperatives of the profit motive?

How does Hollywood create a bogus aura for the actor?

How does capitalism ‘obstruct man’s legitimate claim to being reproduced’?

Benjamin says in Note 29 that Aldous Huxley’s complaint about the production of literary texts is ‘obviously not progressive’. Why? What view of the transmission of literary culture is Huxley upholding in his observation?

XI. Painting vs. Film in terms of the Representation of Reality [263]

The technological equipments and reproducibility have changed the nature of reality and has created new ways of accessing it (deeper and more analytically).

- The equipment-free aspect of reality, difficult to reproduce, has become the height of artifice (the vision of immediate reality has become the Blue Flower in the land of technology).

Painting vs. Film (Film: new and different from the earlier aura-laden art forms)

Magician is to surgeon as painter is to cinematographer/cameraman.

- The enormous difference in the images they obtain: a total image vs. a piecemeal image with its manifold parts being assembled according to a new law [263-64]

- The presentation of reality in film is incomparably the more significant for people of today, since it provides the equipment-free aspect of reality they are entitled to demand from a work of art, and does so precisely on the basis of the most intensive interpenetration of reality with equipment. [264]

XII. The Social Significance of Film Today [264]

The Technological reproducibility of the artwork changes the relation of the masses towards art:

- the masses’ extremely backward/reaction towards a Picasso painting

- the masses’ highly progressive (=positive) reaction to a Chaplin film

Painting—a stand-alone totality; not for collective experience; inviting a viewer to contemplation

Film—lending itself readily to analysis; rendering one to be a critic; overriding contemplation

Popular culture works with hegemonic forces because it is shaped by mass audience’s response in a feedback loop (lack of appreciation of the truly innovative and purposeful art).

An object of simultaneous collective reception/experience:

- Painting by its nature is not; architecture has always been; the epic poem was at one time;

Film is today. [264]

(Film takes over from the epic poem the function that architecture has always played.)

- Collective simultaneous experience, enabled by film, is not possible even in publicly displayed paintings in galleries and salons.

Film enables the masses to organise and regulate their response [264-65]

(Thus, the same public reacts progressively to a slapstick comedy/grotesque film and inevitably displays a backward attitude towards Surrealism.)

How does Benjamin address the way in which the camera changes both the object captured and the viewers’ perceptive capacity?

Do you find Benjamin persuasive when he implies that the future of a technological mode can be glimpsed in the desire it awakens (eg, to reproduce images in an increasingly detailed way—with sound and, ultimately, of course, in colour or with 3D techniques)?

XIII. A Deepening of Apperception by Film [265]

Film: man’s presentation of himself to the camera;

man’s representation of his environment by the camera

Film has enriched our field of perception (Freudian theory of psychoanalysis) through the testing capacity of the equipment (and its increased involvement):

- Analysable things increased throughout the entire spectrum of optical and auditory perception and by distancing from reality (abstraction of perception)

- Film furthers insight into the necessities governing our lives by its use of close-ups, by its accentuation of hidden details in familiar objects, and by its exploration of commonplace milieux through the ingenious guidance of the camera.

- Rapid movement of the camera extends comprehension.

- Film manages to assure us of a vast and unsuspected field of action (travelling).

(With the close-up, space expands; with slow motion, movement is expended. [265])

Through the camera, we first discover the optical unconscious, just as we discover the instinctual unconscious through psychoanalysis. [266]

How does film help overcome the longstanding divide between art and science or technology?

XIV. Shock Effects: Film vs. Dadaism [266]

It has always been one of the primary tasks of art to create a demand whose hour of full satisfaction has not yet come.

Daddaism attempted to produce with the means of painting (or literature) the effects which the public today seeks in film.

- The dadaists attached much less importance to the commercial usefulness of their artworks than to the uselessness of those works as objects of contemplative immersion — a ruthless annihilation of the aura in every object they produced, which they branded as a reproduction through the very means of production (moral shock effect). [266-67]

- Film initiates perception that is involuntary (physical shock effect)

Painting vs. moving images

(contemplation vs. perception which is unconscious, incidental, unreflective but also provides insight into expanded space with close-ups, extended motion with slow motion bursting the prison-world of perception and launching us on “adventurous travelling”)

- “I can no longer think what I want to think. My thoughts have been replaced by moving images.” (Duhamel 1930) [267]

The shock effect seeks to induce heightened attention:

- By means of its technological structure, film has freed the physical shock effect—which Daddaism had kept wrapped, as it were, inside the moral shock effect—from this wrapping.

XV. Reception in a State of Distraction: Architecture and Film [267]

Quantity into Quality:

- The masses are a matrix from which all customary behaviour towards works of art is today emerging newborn.

- The greatly increased mass of participants has produced a different kind of participation.

- The new mode of participation, which first appeared in a disreputable form, was a spectacle which requires no concentration and presupposes no intelligence.

Distraction and concentration [268]

- the ancient lament: the masses seek distraction; art seeks concentration from the spectator.

® moral evaluation of film

- A person who concentrates before a work of art is absorbed by it … .

By contrast, the distracted masses absorb the work of art into themselves.

Distraction of spectacle (consumed by the masses in a state of un-reflection)

vs. Concentration of art (absorption and identification) but What about architecture?

Architecture in terms of Distraction and Concentration

- Architecture has always offered the prototype of an artwork that is received in a state of distraction and through the collective.

® lasting form (unlike historical forms of art such as panel painting)

- Buildings are received by use and by perception, tactilely (by way of habit) and optically (in the form casual noticing).

The sort of distraction provided by art represents a covert measure of the extent which it has become possible to perform new tasks of apperception. Since, moreover, individuals are tempted to evade such tasks, art will tackle the most difficult and most important tasks wherever it is able to mobilise the masses. It does so currently in the film. Film is the true exercise of art today (in 1930s). [268-69]

- Reception in distraction—the sort of reception which is increasingly noticeable in all areas of art and is a symptom of profound changes in apperception—finds in film the true training ground (by virtue of its shock effects). [269]

- The audience is an examiner, but a distracted one.

Why is ‘distraction’ is better than ‘concnetration’ when one is experiencing film or art more generally?

How is it that the masses are able to experience art in a satisfying manner while in what Benjamin calls ‘a state of distraction’?

Epilogue: The Fascist Aestheticising of Politics vs. the Communist Politicising of Art [269]

The increasing proletarianisation of modern man and the increasing formation of masses are two sides of the same processes.

Fascism renders politics aesthetic.

- Fascism attempts to organise the newly proletarianised masses while leaving intact the property relations which they strive to abolish.

- Fascism seeks to give the masses not their right but expression in keeping these property relations unchanged.

- The logical outcome of fascism is an aestheticising of political life

(the Führer cult, apparatus in the service of production of ritual values)

- Only war, in which all efforts to aesthetised politics culminate, makes it possible to mobilise all of today’s technological resources while preserving traditional property relations.

- Fascist glorification of war is the ultimate rendering of politics aesthetic & artistic gratification of a sense perception changed by technology (Futurists celebrate war: see Marinetti’s manifesto)

l’art pour l’art [290]

- Human-kind which once was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, has now become one for itself. The self-alienation of art has reached the point where it can experience its own annihilation as a supreme aesthetic pleasure.

Communism politicises art

- Art has no purpose in totalitarian regimes except to organize rituals of public life

In what way does fascism transform politics into aesthetics? (In what sense did Hitler succeed in crafting himself and People into an aesthetic object?)

Why does this transformation lead inexorably to a society organised entirely around the preparation for and waging of war?

How is it possible that human beings can experience war—a profoundly self-destructive act—as pleasurable?

What warning does Benjamin’s analysis of the Nazis’ success in exploiting film’s potential hold for those who concern themselves with art? Do you think that Benjamin’s Marxist claims about the revolutionary power of the movie camera as a mode of ‘technological reproducibility’ are convincing in the light of such abusive treatment by reactionary movements?

An A to Z of Sussex University Life

(이글 역시 유학시절 홈피를 만들던 후배들을 돕고자 썼던 글인데, 자료 삼아 퍼다논다. http://cafe.daum.net/sussex)

A is for 'Arts Buildings'.

- 인문 사회 과학 분야의 대부분의 학과가 들어서 있는 서로 미로처럼 이어진 다섯 개의 건물. Arts는 중세 대학에서 가르치던 the liberal arts 7 과목에서 유래한 이름으로 현대식 건축물과 묘한 부조화를 이루는 건물 이름이다. 아침에 유럽(Euro Bar)에서 커피를 마시고 오후에는 미국이나 영국(EAM Bar)의 푹신한 소파에서 영국 차를 즐기며 휴식을 취할 수도 있지만 햇볕이 따사로운 봄, 여름에는 아프리카나 아시아(Afras Bar)의 뜰에서 마시는 커피 맛과 다양한 주제의 대화는 잊을 수 없다.

B is for 'Bramber House'.

- 몇 년 전까지 에코의 소설 '장미의 이름'에 나오는 수도원의 식당을 연상시키는 Refectory라고 불리던 건물. 두 층의 식당과 펍, 바 등이 자리잡고 있지만 서점, 동창회, 우체국, 은행, 식료품 가게 등도 있어서 개명의 필요성이 있었다고 한다. 이제 이 건물을 어떤 이름으로 부르느냐에 따라 대학 사회 내에서 세대를 가늠하는 기준이 되어 간다.

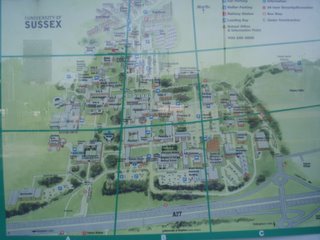

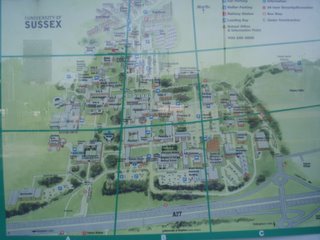

C is for 'Crouching Cat, Hidden Campus'.

- 캠퍼스 안 도처에 세워진 건물 배치도. 기숙사와 스포츠 퍼빌리언을 포함한 캠퍼스의 전체 건물의 배치는 앉아 있는 고양이의 모습이지만 이를 알아차리기까지는 적어도 일년은 걸린다. 마음이 착한..., 아니 마음의 여유가 있는 사람에게만 고양이가 보인다. '눈멂'과 '통찰'은 도대체 무슨 관계일까?

D is for 'DPhil'.

- Acronym과 initialism이 뒤섞인 기형적 표현. 영국에는 원래 대학의 제도로서의 박사는 없었고 다만 오늘날의 명예 박사에 해당하는 명칭이 탁월한 업적을 이룬 기성의 학자에게 주어졌다. 그러던 중 미국이나 영연방에서 유학 온 학자들이 다년간 연구를 한 후에도 빈손으로 돌아가야 한다고 불평을 함에 따라서 현재의 박사 학위 제도를 미국에서 1910년대에 도입했다. 이 사실은 영국의 학위가 대륙에서처럼 강의 없이 연구 업적을 평가하여 주어지는 계기가 된다. 그러나 영국에서는 박사 학위까지 받아 학자로 남는 것을 능력 부족으로 여기던 분위기가 1950년대까지 계속되었다. 재미있는 일화로는 Harvard에서 철학 박사 논문을 쓰던 중 자료를 준비하러 Oxford에 왔던 시인 Eliot가 논문을 제출하고도 학위를 포기하는 사건이 있다. 아무튼 미국에서 박사를 PhD (Philosophiae Doctor)라고 부르기 때문에 Oxford에서는 DPhil (Doctor of Philosophy)로 불렀고, Oxford와는 달라야 함을 가장 중요하게 여기는 Cambridge는 미국에서 사용하는 명칭이어서 불쾌하지만 라틴어라는 점에서 위안을 삼아 PhD로 부르게 된다. Sussex에서는 설립 당시 대학 행정면에서 Oxford를 모델로 삼았다. 일설에 의하면 PhD가 한국에서는 Permanent Head (Brain) Damage 영국에서는 Poverty, Hardship and Deficiency 의 initialism이라 하는데 그렇다면 DPhil은 무엇의 약자일까?

E is for 'Eating like a horse'.

- '먹는 것이 힘이다.' Sussex 한국인 사이에 전해 내려오는 명언 중 하나. '아는 것이 힘'인 지식 권력 사회와는 달리 지식이 권력이 아니고 기본인 유학생의 입장에서는 살기 위해 먹는지 먹기 위해 사는지 분간할 수 없다. 아무튼 먹고 읽고 마시고 쓰다 보면 하루가 가고 또 일년이 간다.

F is for 'Falmer Village'.

- Sussex 대학이 속한 행정구역. 마을 중앙에 한 두 배의 오리 가족들이 한가하게 노니는 연못이 있고 그 연못 한 쪽에는 아담한 교회가 있으며 그 반대편에는 꽤 오래된 목사관이 있는 아름답고 한적한 시골 마을이다. 마을에서 대학으로 내려오는 길목에는 우리 한인 모임을 자주 갖는 펍 Swan Inn이 있다. 삼 대째 가업을 이어오는 자동차 광인 주인은 독신남으로서 맥주 값 계산에는 매우 정확하다.

G is for 'Gardner Art Centre'.

- Gardner라는 사람이 대학에 기증한 아름다운 건물. 평상시에는 외부의 공연, 전시회 등에 대관하고 화제의 영화들도 상영하여 대학 재정의 한 몫을 담당한다. 동계 졸업식이 열리는 건물이다. 이 건물 가까운 지역의 자동차 번호 (신형)도 G로 시작된다 (the Garden of England).

H is for 'Hypocricy'.

영국인들의 속성. 영국 대학에서는 지도교수와의 관계가 논문의 성공에 결정적인 영향을 미치게된다. 대개 지도교수의 평이 '좋다. 계속해라' 정도라면 스스로 신중하게 평가해야 한다. 이는 어쩌면 '네가 하고 있는 일을 아직 종잡을 수가 없구나'이기가 쉽다. 잘 진전되는 경우에는 대체로 지도교수의 표정이 달라지고 요구 사항이 많아지며 제안과 추천 서적 또한 많아진다. 아무튼 영국에서 'Good!'은 칭찬이 아니다.

I is for 'Interdisciplinarity'.

- 학문의 패러다임이 '지혜 (wisdom)'에서 '지식 (knowledge)'을 거처 '정보 (information)'로 이동해가고 있다면 이 시대는 분명 역사상 새로운 경험이다. 하버마스는 현대성의 한 양상으로 서로 담을 쌓은 학문의 세분화를 들고 있는데 이와 같은 비 순수를 이미 경험한 후 공자, 맹자 혹은 플라톤, 아리스토텔레스의 '지혜'의 추구로 돌아 갈 수는 없는 일이다. 이 상황에서 제시된 대안으로서 '학제적 연구'는 많은 가능성을 보여 왔다. 그러나 그 화려한 외관만큼이나 연구자의 영역은 만만치가 않다. 두 학문 사이의 연구란 양쪽의 전문적 식견을 바탕으로 새로운 가능성을 추구하는 일이다. 가령 학위 논문의 경우 그 심사를 양쪽 전문가들이 동시에 하게 되는 경우를 종종 본다. 최근에 성공적으로 통과된 한 한국인의 경제지리학 논문의 경우 지리학자와 경제학자가 심사를 했고 또 최근 실패한 한 일본인의 영문학 논문 (Shelley의 시에 대한 불교적 접근)의 경우 심사위원인 불교 학자가 문제를 제기했다고 한다. 그렇지만 오늘날 각광받는 문화연구, 여성학, EU 연구 등은 모두 학제적 연구 분야들이다.

J is for 'Jack and Jill'.

- 영국에서 사라져 가는 제도로서 결혼. 그와 더불어 '아내', '남편' 등의 어휘도 사라질 운명이다. 그 대신 원래 사업상의 동료인 '파트너'는 새로운 의미를 하나 덧붙여 간다. 이는 이혼율 세계 1위와 더불어서 'Single Mum'에게 주어지는 각종 특혜와 무관하지 않은 사회 현상이다. 그러나 Jill이 Jack없이는 못사는 법인 듯하여 가족 관계에서 'step'이 붙는 표현이 많아지고 나이가 적당히 든 Jill은 'ex-'라는 말을 스스럼없이 많이 쓴다.

K is for 'Koreans at Sussex'.

- Sussex 대학 내 소수 집단 중 하나. EU국가 출신도, 영연방 출신도 아닌 한국인 유학생들의 위상은 다소 초라한 인상이다. 돈 많은 일본인들처럼 영국에서 반기는 것도 아닌데 한국은 영국을 유구한 전통의 나라니 뭐니 하며 짝사랑하는 것은 아닌지.

L is for 'Library'.

- 야트막한 외관과는 달리 의외로 넓은 3층 건물. 120만여권의 장서를 갖춘 개가식 도서관으로 대학의 역사에 비해 19세기와 20세기초에 출판된 책들도 비교적 잘 갖추고 있지만 주변의 많은 명망가들이 죽으면서 기증한 도서들이 그 간극을 계속 채워가고 있다. 한편, 학생이 연구를 위해 원하는 책이 도서관에 없다면 그것은 전적으로 도서관의 책임이라서 새로 구입을 하거나 구입할 수 없는 경우에는 타 도서관에서 비용을 들여 빌려다 준다. 또한 개가식 도서관의 장점은 필요한 책을 찾으러 서가에 들어갔다가 바로 옆에 꽂힌 책들도 함께 들추어 볼 수 있다는 점인데 그러는 중에 연구의 방향이 보다 세련되어 감을 경험하게 된다.

M is for 'MA or MSc'.- '일년밖에 안되는데 뭘!'하고 덤볐다가 많이들 후회하는 과정. 상대적으로 영어가 서툰 (영국에서의) 첫해에 필독량이 많고 세미나에 공헌해야 할 의무감에 시달리다 보면 어쨌든 한 해가 간다. 석사과정이 한국에서는 중요하게 여겨지지만 영국에서는 대체로 학문을 계속할 것인지 탐색하는 기간 정도로 생각한다. 영국에서도 요즈음은 석사를 권장하는 분위기이지만 학부 졸업 후 바로 박사 연구 과정을 시작할 수도 있다. 석사과정을 일단 시작하면 그 성적은 박사 진학을 위해서는 매우 중요하다. Sussex 혹은 Oxbridge에서 박사를 하려 할 경우는 일정 수준 이상의 성적에 미달할 경우에는 입학이 취소된다. 그래도 영국 학위를 원한다면 외국인에게 특히 관대한 W대학 등이 있으므로 크게 걱정하지 않아도 되겠지만 그 대학에서는 졸업도 쉽다는 이야기는 아니다.

N is for 'Nobel Prize'.

- Sussex 대학과 노벨상의 인연은 큰 편이다. 수상한 전직 혹은 정년 퇴임 Sussex 학자들은 상당수에 이르며 현직으로는 화학과에 한 명이 있다.

O is for 'October'.

- 공부밖에 할 일이 없는 계절의 시작. Brighton에는 절묘하게도 시월이 되면 비가 내리기 시작한다. 그것도 매일. 한국에서는 놀기 좋은 봄과 더불어 학기가 시작되어 학문에의 정진이 바로 수양임을 일깨우는데 이 곳에서는 여름 동안 실컷 놀고 어쩔 수 없을 때 공부하는 셈이다.

P is for 'Pond'.

- Sussex 대학 건축가의 집착. 그는 애초에 캠퍼스 중앙에 인공 호수를 만들려고 했으나 재정상 포기를 강요당했다. 그러나 그는 물이 없는 환경에서 학문을 한다는 것을 상상할 수 없었고 궁여지책으로 건물 주변과 사이사이에 연못을 만들기로 했다 한다. 캠퍼스 안에 연못이 몇 개인지를 정확히 아는 데도 아마 일년은 지내야 하지 않을까?

Q is for 'Queer'.

- 전혀 이상하지 않게 여겨지는 동성애. Brighton이 영국에서 동성애로 유명한 만큼 Sussex대학에는 동성애 연구로 유명하다. 게이 교수들과 함께 공부하는 게이 학생들은 사랑으로 무장된 집단이다. 어떤 레즈비언 교수는 남자에게 눈도 마주치지 못할 만큼 수줍음이 많다. 게이나 레즈비언이 이상한 사람들인지 혹은 이들을 이상하게 보는 사람들이 이상한 건지.

R is for 'Red brick'.

- 돌이 없는 Sussex지방의 대표적인 전통적 건축 자재. 자연스럽게 대학 신축 당시 이를 사용하여 'Red brick University'가 Sussex대학의 별명이 되고 나중에는 새로운 대학을 의미하는 보통 명사로 전용되어 붉은 벽돌과는 무관한 Essex, York, Keele, Warwick 대학 등도 같은 이름으로 불리게 된다.

S is for 'Sussex'.

- 'Sir Sex!'가 되지 않도록 발음상 주의를 요하는 이름. Sussex대학에 유학생 자녀를 둔 한국의 많은 부모님들이 자식의 학교를 쉽게 자랑하지 못하는 당혹스러움을 경험하신다. Sussex는 사실 Sex와는 무관(?)하고 원래 Saxon족이 거주하던 영국의 남동부 지방, 즉 Essex, Middlesex, Wessex, Sussex 중에서 South를 의미한다.

T is for 'Tennis'.

- Sussex 한인 사회에서 가장 활발한 스포츠. 원래 한국 테니스 계에서는 고수들이 초보자들을 노예 취급하지만 여기서는 사람이 귀하다 보니 왕초보라도 잘 가르쳐서 데리고 논다.

U is for 'University Ranking'.

- 한국인들의 초미의 관심사. Sussex 대학은 설립 당시부터 전국 5위권을 유지해 왔지만 최근 들어 다소 부진을 면치 못한다. 정부에서는 재정 지원의 자료로 삼기 위해 매 5년마다 교수의 연구 성과와 학생의 졸업률을 조사하는데 학부의 경우에 전국 180여개 대학 중 Sussex 대학은 1996년에 12위였다가 2001년에는 31위로 하락하였다. 그런 와중에도 심리학, 화학, 생물학, 물리학, 응용 수학, 컴퓨터 과학, 일반 공학, 미국학, 영문학, 미술사학, 음악, 교육학, 철학, 사회인류학, SPRU 등의 분야에서는 최상위 평점인 5를 받았다. 특히 2001년 평가에서는 Oxbridge를 제외한 여타 대학들의 경우 특정한 몇몇 분야에서만 상위 평점을 받은데 반해, Sussex는 거의 전 분야에서 5점 이상을 받아, 대학 당국은 물론 학생들도 자랑스러워하고 있다.

V is for 'Viva Voce'.

- 논문 구두 시험. 미국에서는 defence라고 불리는 데 그 저변에 놓인 발상의 차이가 재미있다. 미국 대학에서는 시험관의 '공격'을 요령 것 '방어'할 것을 기대한다면 영국 대학에서는 박사 논문을 완성했다 해도 여전히 시험 대상인 학생에 불과하다. 또 다른 차이로는 미국에서 석사논문을 thesis, 박사논문을 dissertation이라 부르는 데 영국에서는 그 반대의 명칭을 사용한다. 아무튼 논문이 통과되면 'Viva!'

W for 'Woolf'.

- Virginia Woolf. 대학에서 자동차로 20분 정도 떨어진 중농 정도의 마을 Rodmell에 시골집 (런던 밖의 휴가용) Monk's House를 갖게 됨으로써 그녀의 사후에 설립된 Sussex 대학과 인연을 맺게 된다. 그녀가 이 곳에 머무는 동안 신경쇠약의 강박관념으로 동내 앞 Ouse 강에서 자살을 한 후에도 남편 Leonard는 그 집을 계속 유지했으며 문인들과 Virginia 사이의 서신들 중 일부(미간행)를 훗날 대학 도서관에 기증한다. 그녀로 인해 Sussex 대학은 오늘날까지 modernism의 연구가 가장 유명한 대학 중 하나로 자리 매김하고 있다. 한편, Monk's House는 지금은 the National Trust의 소유이지만 수요일과 토요일 오후에만 일반인에게 공개된다.

X is for 'Xerox machines'.

- 매사에 정확한 척하는 영국인들은 photocopier라고 부르는 복사기. 한국인들이 처음에는 당황할 수밖에 없는 도서관의 복사비(장당 6p)는 그래도 the British Library보다는 싸다 (면당 20p). 한국에서보다 터무니 없이 비싼 이유는 바로 저작권료 때문이다. 영국에서 학술도서를 저술한 사람은 누구나 매년 저작권료를 각 대학으로부터 학생수에 따라 다르게 받는다고 한다. 현재 총장 협회에서는 이 비용을 줄이려하고 저작권 협회에서는 인상하려 하여 갈등을 겪고 있다. 그래서 도서관 밖의 복사비가 다소 싼 편이다 (5p in Arts D).

Y is for 'Yum-Yum'.

- 맛있는 소리. Brighton시내 North Lane에 있는 중국 식료품 가게 이름이기도 하다. 시내의 한국 식품 가게가 영락을 거듭하는 중에도 이 중국 점은 꿋꿋이 버티고 있어 주목거리이다.

Z is for 'Zest'.

- Last but not least, zest for life! 이 보다 중요한 것이 있을까? 오늘도 해변의 캠퍼스에는 바람이 ... 아니 비가 내린다. 살아야겠다. (무슈 발레리, 표절 미안!)